Press

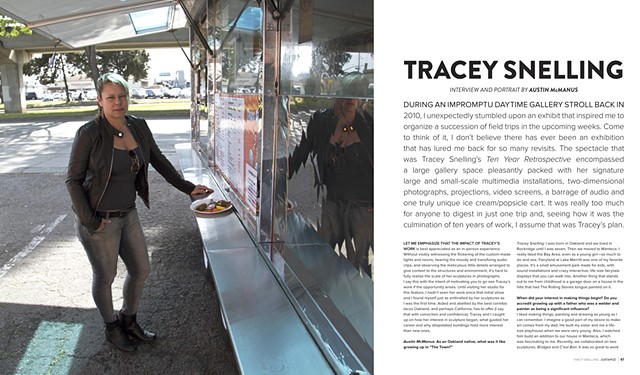

TRACEY SNELLING

INTERVIEW AND PORTRAIT BY AUSTIN McMANUS

DURING AN IMPROMPTU DAYTIME GALLERY STROLL BACK IN

2010, I unexpectedly stumbled upon an exhibit that inspired me to

organize a succession of field trips in the upcoming weeks. Come

to think of it, I don’t believe there has ever been an exhibition

that has lured me back for so many revisits. The spectacle that

was Tracey Snelling’s Ten Year Retrospective encompassed

a large gallery space pleasantly packed with her signature

large and small-scale multimedia installations, two-dimensional

photographs, projections, video screens, a barrage of audio and

one truly unique ice cream/popsicle cart. It was really too much

for anyone to digest in just one trip and, seeing how it was the

culmination of ten years of work, I assume that was Tracey’s plan.

LET ME EMPHASIZE THAT THE IMPACT OF TRACEY’S

WORK is best appreciated as an in-person experience.

Without visibly witnessing the flickering of the custom-made

lights and neons, hearing the moody and transfixing audio

clips, and observing the meticulous little details arranged to

give context to the structures and environment, it’s hard to

fully realize the scale of her sculptures in photographs.

I say this with the intent of motivating you to go see Tracey’s

work if the opportunity arises. Until visiting her studio for

this feature, I hadn’t seen her work since that initial show

and I found myself just as enthralled by her sculptures as

I was the first time. Aided and abetted by the best carnitas

tacos Oakland, and perhaps California, has to offer (I say

that with conviction and confidence), Tracey and I caught

up on how her interest in sculpture began, what guided her

career and why dilapidated buildings hold more interest

than new ones.

Austin McManus: As an Oakland native, what was it like

growing up in “The Town?”

Tracey Snelling: I was born in Oakland and we lived in

Rockridge until I was seven. Then we moved to Manteca. I

really liked the Bay Area, even as a young girl—so much to

do and see. Fairyland at Lake Merritt was one of my favorite

places. It's a small amusement park made for kids, with

sound installations and crazy interactive, life-size fairytale

displays that you can walk into. Another thing that stands

out to me from childhood is a garage door on a house in the

hills that had The Rolling Stones tongue painted on it.

When did your interest in making things begin? Do you

accredit growing up with a father who was a welder and

painter as being a significant influence?

I liked making things, painting and drawing as young as I

can remember. I imagine a good part of my desire to make

art comes from my dad. He built my sister and me a life-

size playhouse when we were very young. Also, I watched

him build an addition to our house in Manteca, which

was fascinating to me. Recently, we collaborated on two

sculptures, Bridges and C'est Bon. It was so great to work

with him! Since he lives an hour and a half away, we talked

about the work and sketched; he built the sculptures, and

I finished them with paint, landscape, video, lights

and electronics.

While attending the University of New Mexico, you

discovered sculpture as a new outlet for your creative

process. Do you remember a defining moment when more

of your attention became focused on this newer medium,

or was it more gradual?

I did experiments with sculpture at UNM, although the

defining moment came later. A few of the works I made at

UNM that stand out are a twisting mountain/cliff sculpture

with a small lit room on top, referencing a Dorothy Parker

poem, and a series of dangerous jewelry made in my small

metal fabrication class. The jewelry had spikes, and either

kept people at a distance, or, if reversed, would harm the

wearer. I really liked combining the conceptual idea with the

pieces, but I was chastised by the professor for doing such

dark work! Sculpture became an integral part of my work

in 1998 when I was inspired by a collage of mine to build

a three-dimensional house sculpture, completely covered

with collage and wired with lights.

I have an affinity for New Mexico and the region. The

topography, the culture and especially the food, is so

unmistakable. What was your experience living there?

I chose New Mexico because of the reputation of UNM's

photography department, and even more so for the mood

of New Mexico. I felt like I was living in a film noir movie at

times. The large expanse of skies, dusty brown littering of

adobes, green chili and the slow pace were fascinating to

me. One time, while scouting for a photo shooting location,

I came across a weed and litter-strewn empty lot with a

large side of beef, complete with ribs, encased in a plastic

bag, roasting/rotting in the sun. Strange things like this

seemed to happen all the time in Albuquerque.

While in school, you worked seasonally in the forest

service, correct?

I was a wildland firefighter for three fire seasons, putting

myself through school. It was a very exciting job, never

the same on any day. After a while, the adrenaline rush

becomes something you miss, and the smell of fire is a

welcome scent. It was ideal, at least for the time being,

as I always abhorred a regular job, having to do the same

tasks every day.

Do you photograph all your sculptures in real outdoor

environments, and what is your intention in doing this?

When I was at UNM, I had a small old house that I

photographed out in the environment, and I liked the

outcome. I had done some interior tableau photography and

preferred the feeling of using the real, outdoor environment

as the background. It felt less claustrophobic. For a long

time I photographed most of my sculptures in this manner.

But at some point I wasn't enjoying it anymore and stopped.

I started photographing them again when it felt interesting

once more. Now I just do it occasionally, when the feeling

strikes me. When I photograph one of my sculptures in the

outdoor environment, I'm giving it a place and mood. Mood

is very important in these images. It gives the sculpture

a different narrative, but also freezes it in time and place.

When one observes the actual three-dimensional sculpture,

it is more like a three-dimensional film, and time and place

are more fluid. I've since taken the idea of photographing

the sculptures out in the environment a step further by

shooting videos. Late last year, I made a film, The Stranger,

along with collaborator Idan Levin, using the sculptures as

the sets and green-screening an actor into the scenes.

Do you solely use building materials, or do you incorporate

found materials as well?

I primarily use building materials, but at times I also use

found materials, such as toys or props found at flea markets,

antique or dollhouse and model train stores. In Beijing I

used some of the leftover firework remnants and scraps

of material in a pile of rubble near the gallery. For the new

installation that I'm presently working on, One Thousand

Shacks, I'm using lots of found material to finish the work.

The installation addresses global poverty, and the use

of materials such as old food containers and cardboard

echoes the importance of found material in building the

living spaces in impoverished areas.

At what point did you start to incorporate light, audio and

video into your sculptures?

Around ’98 or ’99 I began to incorporate light and sound.

Piecing together the audio soundtracks was very similar

to when I would make collage. For both mediums, I start

by collecting images in magazines and audio clips off the

internet. I then start piecing it together and fill in the holes

at the end with more material that I need to search for again.

In 2004, I incorporated my first video into a sculpture. It

was quite complex, made of found movie scenes and video

that I shot of my sculptures, with a collaged soundtrack.

The thing I like about more complex audio and video work

is that I can get lost in it. I've also occasionally used motors

for movement, real water in sealed "ponds" and "rivers," and

even smell in my sculpture called Alley.

Is there a type of architecture that particularly

fascinates you?

I continually find myself attracted to older buildings.

Often the buildings would be considered banal, as the

architecture may not at all be complex. Sometimes the

building that I choose or invent is more about the purpose

than the actual architecture, such as a strip club or mini

mart. When traveling in different countries, I still find myself

attracted to the older, more dilapidated buildings than the

new, clean ones. Still, at some point, I might choose to look

at the newer facades and the wealthier population. The

interesting thing with this is that these people still have as

many problems as those who are less fortunate, but there’s

often a cover of shiny veneer to masquerade it.

In my opinion, one of the best features of your

sculptures is the use of hand-painted signs and neons.

They communicate a lot about a place culturally and

economically. What is your attraction to them and what do

they represent to you?

I've always been attracted to old hand-painted and neon

signs. Even better is when someone paints the name of their

business on their building along with painted images, such

as a woman with a fancy hairstyle for a small-town beauty

salon. Hand painted signs can be found in just about every

culture and place and have so much character. They often

can capture the essence of a place.

I also really appreciate that you have incorporated graffiti

into a number of your cityscapes. It’s a subtle touch but

adds a lot of character. What initially inspired you to start

doing this?

I've always liked how graffiti looks, and in some of the

settings, the graffiti is an integral part of the location. I feel it

makes the buildings look more realistic. I've never learned

how to do graffiti, so I find samples online or take a photo

and reproduce it by painting it or printing it out. For my

sculpture The Fall, which addresses the global outcome

if pollution and neglect of the environment continues, I

painted graffiti on the bottom part of the sculpture. The

graffiti was from images in Chernobyl and photographs I

took in Israel.

Even amid audio and flashing lights, your installations can

evoke a sense of desolation and loneliness. Could that

be because these ordinary places are familiar to all of us,

regardless of background?

It can, in part, be attributed to the fact that we all know

these places. Even more so, at the core of my work is the

examination of the human condition: the struggle, longing,

beauty and disappointment that we all face as we try to

make our ways through life. I'm also attracted to film noir,

fallen heroes and stories that don't always have a happy

ending but rather, maybe, continue on in mundanity or end

with a dilemma. This attraction seems to carry through in

my work.

What do you believe has been the most rewarding aspect

of your creative endeavors?

Besides actually getting to be in my studio and make work

all day that I love, the travel and the people I have met are

two great rewards from my art career. It's such a different

experience to visit a place while installing or showing my

work and to meet and get to know all the people who are

involved—curators, collectors and artists. As opposed to

showing up to a place as a pure tourist, I get to experience

a place and culture from a different viewpoint. I've made

some of my closest friendships through these exchanges.

With motels being a recurring motif in your work, I’m

reminded of a motel off the freeway in West Texas where

I stayed last year. Upon opening the door in morning, I

was greeted by thousands of dead roaches and there was

a man whose job was to casually sweep them up every

morning. It was surreal and my most memorable motel

experience. Can you explain their allure for you, as well as

any good stories from your motel stays?

That's quite an experience to have dead roaches outside

your door! Very surreal. I've been attracted to motels since

I was a young girl. I like the sense of travel and freedom, but

even more so the idea of a place that has an ever-changing

cast of characters. There are so many stories and history

in a single motel. Who stayed there? What did they do in

the room? I like to think about the various things that might

have happened. Usually it's not so extreme. Maybe a couple

stayed as they were traveling across country to relocate

and had an argument, so they watched some bad movie

and didn't speak to each other the rest of the night. Or

some people stayed and did drugs till the morning. Another

couple might have the motel room as their only place to

rendezvous. The variations of stories are never ending.

Once, while staying with an old boyfriend at a motel in

Southern California near the desert, we awoke to loud

knocking and a man yelling, "Let me in! I know you're in

there!" The door didn't even have a deadbolt, just a knob

lock and flimsy chain. We couldn't dial out, we could only

call the motel office and no one was answering. We couldn't

see who was out there either. This happened several times

in an hour. We wedged a chair under the doorknob and

eventually fell asleep. In the morning, no one was outside.

I used to try to stay at the old motels that are similar to what

I build, but now it's rare that I do. They're often very dirty

and can have questionable guests. But I still would like to

stay in this one motel that has a drive-in that you can see

and hear from your room. I think it's in Arizona.

For more information about Tracey Snelling, visit traceysnelling.com